Summary

Historically, the diamond industry was structurally flawed – the De Beers monopoly controlled prices. But, with peak market share reaching almost 90% in the late 1980’s, a series of events over the next 25 years led to the erosion of the De Beers monopoly. Today, De Beers no longer has control of the diamond industry, and for the first time in a century, market supply and demand dynamics, not the De Beers monopoly, drives diamond prices.

In the late 19th century a massive diamond discovery in South Africa prompted a diamond rush. Businessman Cecil Rhodes bought as many diamond-mining claims as he could, and his accumulation of properties eventually became De Beers Consolidated Mines Limited. De Beers maintained a hold on what was a relatively small industry at the time by expanding from mining into every facet of the diamond industry, with a focus on monopolizing distribution. De Beers successfully influenced just about all of the world’s rough suppliers to sell production through the De Beers channel, gaining control of global supply. This gave De Beers the power to influence diamond supply and thus diamond prices.

The De Beers distribution channel, operating under the unassuming moniker Diamond Trading Co. (DTC), was a system put in place that gave De Beers complete control and discretion to distribute the majority of the world’s diamonds. Only buyers or “Sightholders” authorized by De Beers could participate in the non-negotiable DTC sales.

In order to maintain a stable but rising diamond price, De Beers had the power to stockpile inventory in a weak market or raise the prices charged to Sightholders, and then in an excessively strong price environment (with the potential to damage demand), De Beers had the excess supply on hand to release to the market when needed, repressing disorderly price increases.

To keep the DTC system intact, it was necessary for De Beers to maintain control of the world’s rough diamond supply. However, in the second half of the 20th century, as new world-class mines were discovered in Russia, Australia, and Canada, it became increasingly difficult for De Beers to control global supply. The biggest risk to the survival of the De Beers cartel was for these new world-class mines to begin selling directly to the market, bypassing De Beers.

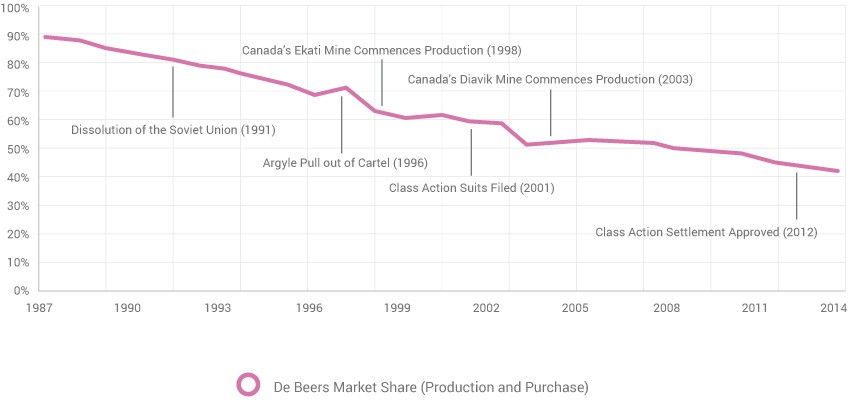

Russia began producing diamonds in the 1950’s. At first, the Russians agreed to sell production to De Beers keeping the cartel intact. However, the arrangement was weakened in 1963 when Anti-Apartheid legislation restrained the Soviet Union from dealing with a South African company. Further pressure came during the Soviet Union collapse in the 1990’s, when political chaos and a weak ruble further separated Russia’s production from De Beers. The De Beers market share began to fall from a peak of almost 90% (See Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

Shortly after losing control of the Russian supply, the Argyle Mine in Australia (at the time the largest diamond producing mine in the world by volume) broke away from De Beers because of the cartel’s inflexibility. Over the next few years, other mines followed suit, as new world-class mines in Canada chose to sell their supply independent of De Beers.

In an effort to maintain control of supply, De Beers began buying diamonds in the secondary market at a premium, but the strategy was short-lived as the cost was prohibitive. By the end of the 1990’s, De Beers’ market share had fallen from as high as 90% in the 1980’s to less than 60%. In 2000, De Beers announced a shift in strategic initiative focused on independent marketing of the De Beers brand, implying that they no longer had control of the market.

In 2001, several lawsuits were filed in U.S. courts alleging that De Beers “unlawfully monopolized the supply of diamonds, conspired to fix, raise, and control diamond prices, and issued false and misleading advertising.” After multiple appeals, in 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court denied the final petition for review, and a settlement in the amount of $295 Million with an agreement to, “refrain from engaging in certain conduct that violates federal and state antitrust laws,” was finalized.

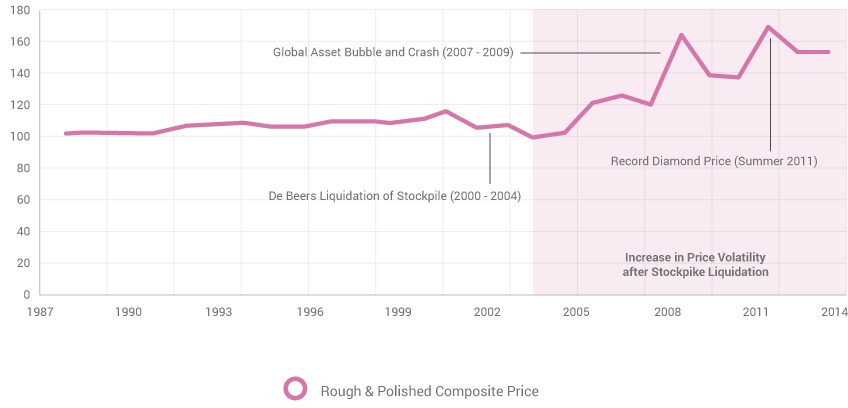

Figure 1.2

The way that De Beers did business, revolving around the central concept of controlling market supply, was simply not viable in a more competitive environment. With the company restructuring underway, De Beers liquidated their stockpile from 2000 to 2004, resulting in a modest decline in diamond prices as the liquidation supply more than offset new demand coming out of Asia (see figure 1.2). By 2005, the inventory overhang had been exhausted allowing market forces to drive diamond prices for the first time in a century, resulting in unprecedented price volatility. Diamond prices made a new high in 2007, followed by a violent sell off in 2008 and 2009 before rebounding to another new high in the summer of 2011. As of June 2013, diamond prices are approximately 15% off the 2011 highs, but remain firm as lower than expected mine output has subdued supply supporting prices.